Biology students contribute to international database

Four senior Biology majors researched plant-pollinator interactions with Assistant Professor Holly Martinson for the eight-week Student-Faculty Collaborative Summer Research Program. They shared data from their rain-or-shine field work with the international Nutrient Network project while learning the skills that all ecologists need to know.

This summer, Matthew Hodgdon, Sophie Gilbart, Hailey Grzemkowski, and Assistant Professor Holly Martinson conducted pollinator research at the McDaniel Environmental Center. Senior Lavi Hotea conducted research with the group in the spring.

Four Biology students working with Holly Martinson, assistant professor of Biology, have conducted weeks of pollinator research as part of the donor-funded Student-Faculty Collaborative Summer Research program, through which they’ve joined a community of like-minded entomologists.

In a patchwork field at the McDaniel Environmental Center (MEC), McDaniel Biology seniors Sophie Gilbart, Hailey Grzemkowski, Matthew Hodgdon, and Lavi Hotea have spent hours observing insect interactions with wildflowers.

Gilbart using an aspirator.

Far from being a relaxing pastime, the students’ experiments require 20-minute increments of hyper-focus and quick reflexes to identify known insects and capture unknown ones to study in the lab.

The students’ commitment to research perseveres through hot, humid, and sometimes rainy conditions while they record data on pollinators and flowers in 5-by-5-meter plots of “old field,” an ecology term for uncultivated land.

To capture candidates for closer study, the students use bug nets or aspirators — a tool with a tube connected to a canister, which they use to gently suck up insects using their breath. When they aren’t using them, the students wear the aspirators hooked over their necks like a doctor’s stethoscope.

While each senior is conducting individual research and helping to build a pollinator database with Martinson, they are also contributing to an international grassroots project called the Nutrient Network: A Global Research Collective.

The project focuses on the effect that certain nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorous, have on local ecology around the world. As a “distributed experiment,” scientists share data within the network to form a large-scale data set. The data is helpful in identifying how human intervention is changing the environment, such as how fertilizers alter plant growth or insect populations.

“The students are interested in getting research experience, but they’re also aware that pollinators are in decline,” says Martinson. “We’re working to understand how pollinators and plants are interacting, because it’s worth figuring out what promotes pollinator abundance and diversity.”

Hodgdon uses a bug net to capture specimens too large for an aspirator.

The project started at McDaniel after Martinson joined the Nutrient Network in 2018. She prepared plots of land at the MEC to receive different nutrient treatments, which creates the patchwork appearance of the land. The plots are treated with nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, a combination of all three, or none. Some plots are ringed with eight-foot-tall wire fencing, to exclude deer from grazing.

Although the treatments cause visible differences in the growth of each plot, intensive study is required to see how pollinators and flowering plants are affected. Besides providing data to the Nutrient Network, Martinson’s lab is contributing to their own in-house, long-term data set that will show the effects of nutrient treatments and fencing over time.

Carroll County has a significant amount of agricultural land, as well as wooded and suburban areas, which is ideal deer habitat. Martinson, who studies habitat fragmentation, urbanization, and biodiversity, knew it was a perfect fit for a Nutrient Network study.

“We count the flowers and identify the species of plants that are flowering, which gives us a sense of the resources available and how they might have been impacted by the nutrients or the deer,” says Martinson. While some plots have very few flowers (or “floral units”) at a time, others will have over 2,000.

Besides joining a global community of scientists, the students formed connections within their lab while engaged in the research.

Grzemkowski recording plant pollinator interactions.

Grzemkowski of St. Mary’s County, Maryland, is studying spiders that use flowers as predation sites. “We see predation happening on top of flowers, and it’s rare but worth noting. Is the spider eating an herbivore that could hurt the plant? Or is it eating a pollinator that would have helped the plant?” says Grzemkowski, who plans to get a Ph.D. in the future.

“I’m aiming to get the life skills and experiences that come with this research, because it is so pivotal for the types of things that I want to do, and to have that at an undergraduate level is vital,” she added.

Gilbart of Taneytown, Maryland, is studying native bee species like Ceratina, also known as small carpenter bees. “I’ve been looking at whether bee genera have preferences in terms of what flowers they’re landing on,” says Gilbart. As she explains, when a plant is described as bee-friendly, the bee referred to is often a large honeybee or bumblebee, which excludes smaller genera and species.

“Ceratina are around 6 millimeters long and have short tongues, so the flowers that big bees visit aren’t as beneficial to these very tiny bees,” says Gilbart.

Now in her second year of conducting summer research with Martinson, Gilbart presented her 2021 research, “Effects of provenance on per-floral-unit pollination rates in a Maryland old-field community,” at the Entomological Society of America’s Eastern Branch Conference in April. Previously, Gilbart won first place for her presentation in the “P-IE: Pollinators and Ecology” undergraduate division at the 2021 Entomological Society of America conference.

Gilbart hadn’t known if field work would be right for her but came to love it through the summer student-faculty research. “I’ve learned broad skills, tools, and knowledge that are important to have as an ecologist, and I’ve learned what an ecologist actually does.”

Hodgdon, who is from Mount Airy, Maryland, is studying “whether floral height changes the amount or abundance of species that will visit,” he says. “I’m going to do field work in the future, so this matches what I want to do with my major. It’s also a really enjoyable work experience.”

Hotea of Westminster, Maryland, was primarily involved in research in the spring, and is comparing observations of early season flowers with mid-season flowers.

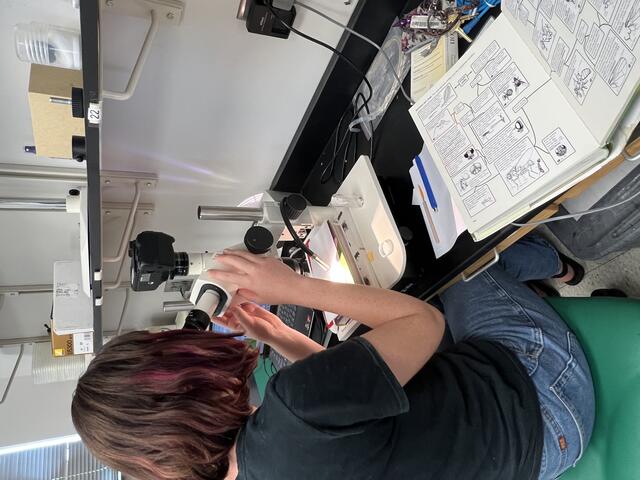

Gilbart examining insect specimens in the lab.

When they aren’t in the field, the students are in a sunny lab in Eaton Hall, finalizing their data and identifying specimens.

Using a microscope and an insect encyclopedia, Gilbart sometimes spends hours identifying species, which are stored in a freezer until it’s their turn under the microscope.

Hodgdon and Grzemkowski can be found entering hand-written field recordings into spreadsheets or using pins to mount caught insects, an initiative the students began this summer to create a reference archive. “If there’s a question about one of the species we shared with the Nutrient Network, we can go back to confirm,” says Hodgdon.

“This summer research is immersive. Students have a lot of ownership over it; I like to have everybody have their own part of the project,” says Martinson. “They need to be nimble with how they are doing the science because life throws all sorts of curve balls. So, they’re troubleshooting, they’re collaborating, they’re working together every day. We have a great community in our summer research lab because everybody is working near each other, helping each other out. That’s how science goes."