Technology empowers students to make environmental impact half a world away

In the dark of night, deep in the Peruvian Amazon last summer, a rare black jaguar prowled along a path through the remote Ichigkat Muja-Cordillera del Cóndor National Park. As the black otorongo stalked its prey, the big cat triggered a series of events that would ultimately lead to its discovery by students in professor Jason Scullion’s “Conservation Biology” class a half a world away.

In the dark of night, deep in the Peruvian Amazon last summer, a rare black jaguar prowled along a path through the remote Ichigkat Muja-Cordillera del Cóndor National Park. As the black otorongo stalked its prey, the big cat triggered a series of events that would ultimately lead to its discovery by students in professor Jason Scullion’s “Conservation Biology” class a half a world away.

In the dark of night, deep in the Peruvian Amazon last summer, a rare black jaguar prowled along a path through the remote Ichigkat Muja-Cordillera del Cóndor National Park.

As the black otorongo stalked its prey, the big cat triggered a series of events that would ultimately lead to its discovery by students in professor Jason Scullion’s “Conservation Biology” class a half a world away.

It would be the first ever recorded black jaguar in Peru’s Amazonas state — made possible through a three-year collaboration between McDaniel College, the National University of Amazonas and Peru’s National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNANP) to establish a biological monitoring program in the park. Word of the sighting went viral on social media and in newspapers all over Peru.

But, exciting as it may be, the black otorongo is just part of the story. By analyzing photos from 19 motion-activated camera traps Scullion helped deploy last summer, the class identified a wildlife hotspot in the northern sector of the 218,000-acre park and 1,100 unique animal sightings, including an ocelot mother and kitten. Among the species included on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of threatened species are the giant anteater, Brazilian tapir and three big cats — ocelot, jaguarondi and jaguar.

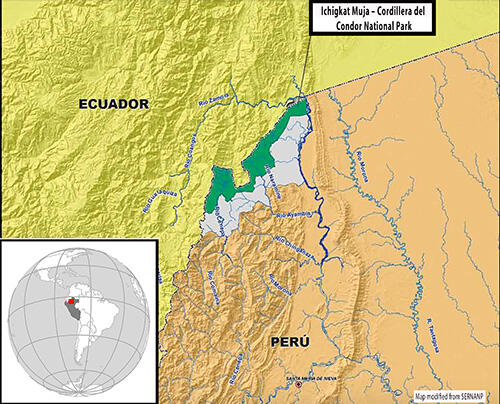

Map of Condor National Park.

The team of freshman Samson Grunwald of Los Angeles, sophomore Biology major Kathryn Dixon of New Bern, N.C., and junior Environmental Studies major Jackie Fahrenholz of Scotch Plains, N.J., identified the hotspot.

“We noticed a high concentration of animals in one area — an abundance of predators and prey in 100 days, 17 species of mammals,” said Dixon, who plans a career in public health and is interested in the impact ecosystems have on people’s health. “Many of the animals are high priority, and some are threatened.

“We also saw lots of photos of the same annoying agouti, a little squirrel-like animal, that kept setting off the camera trap.”

Fahrenholz, who did an independent study in July at the Borneo Nature Foundation in Indonesia and wants to someday work in the conservation field, hopes the black jaguar sighting will lead to improved protection for the wildlife within the park.

“Maybe officials can get attention for the park by telling everyone that this is the park with the rare jaguar,” said Fahrenholz, explaining that working on a real-life conservation project and having an actual client takes her studies to a whole new level.

Working in teams, the students developed wildlife studies that evaluated some aspects of species diversity, presence/absence or distribution using the collected imagery. By evaluating the diversity and occurrence of mammal species, the teams developed a master species list, data on location of mammals in the park and provided recommendations for the management of the park.

What’s more, the students’ conservation work will make a real impact. Their work is conservation in action. It matters, and that’s important to Zach Carnegie, a junior Environmental Studies major from Westminster, Md.

“This experience of actually conducting research and developing a plan has been incredible,” says Carnegie, who wants to apply his Environmental Studies focus on biology to forest ecology, particularly along rivers. “It’s helped me realize just how important camera trapping is and to know how and what you need to be successful.

“Camera traps can not only provide a baseline but they enable us to track the effects of restoration by seeing more and more wildlife return to an area.”

Professor Jason Scullion and park guard Jose Tercero

In fact, camera traps are a relatively new yet invaluable tool for environmental scientists, according to Scullion, whose two-week expedition — including three days in and three days out to a remote rain-forest region to deploy the traps deems it too risky for students. Students who want to experience the Amazon often take McDaniel’s The Forest Online course that features a two-credit Jan Term trip to Peru’s Las Piedras watershed region of the Amazon rain forest book-ended with seven-week one-credit seminars in the fall and spring semesters.

Short of an actual expedition into the Amazon, camera traps, refined in the past decade, can take students to these wild places while helping scientists map their biodiversity.

Scullion designed the class-based experiential learning project to allow his students to be an active part of park management. By using technology and the power of globalization, the students can supply much needed people-power and technical expertise to help evaluate and perhaps conserve rain forest biodiversity.

“The students are all writing policy-based memos to inform an actual client based on real data they collected and analyzed,” said Scullion, explaining that the student projects require them to integrate all they have learned in the course about conserving life on Earth. “They’ve learned about the environmental and social challenges facing wildlife. This gives them an opportunity to practice those skills and see how to apply that to management.”

Conservation Biology students (l.–r.) Zach Carnegie, Jackie Fahrenholz and Kat Dixon show photo of a rare black jaguar captured on camera while prowling in Peru's Ichigkat Muja-Cordillera del Cóndor National Park.